The Cult of White Supremacy

Sidearm: The Cult of White Supremacy

I first met Talia sometime in 2023 through mutual friends. It was a small gathering of aging alt kids: ex-goths, punks, and other weirdos. It was a pleasant, revolving door hangout at YEG’s most graffiti-laden pizzeria-slash-korean-food-joint, Steel Wheels.

At first, she seemed very apprehensive. Meeting new people is like that. You start off in the casual fencing match of ‘who do you know’ and ‘what kind of person are you? What’s safe to talk about around you?’ I understand this dance more than most people. But after a few happy hour coronas, we got to talking.

We talked about makeup, about horror movies, about sex work, about equity, direct action, and community. I think, for our first meeting, it took a while to talk about body mods and tattoos.

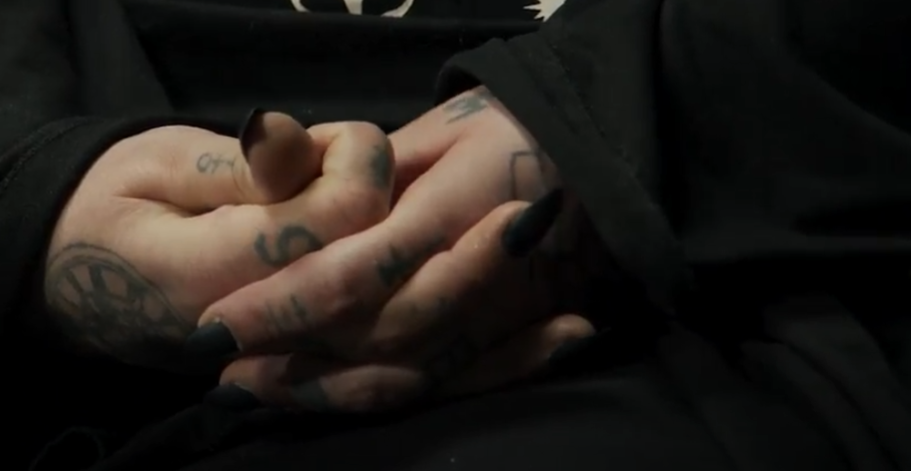

That’s something most people would notice about Talia at first. She is absolutely covered: face, hands, forehead, neck, chest, all from different eras of her life. Artifacts of where she’s been. And who.

We all carry mementos like these, I think. Inside and out.

Several months passed. We grew close. I learned a little more about her. We went to some of the same parties - - sometimes even on purpose. I’d bother her to steal some second-hand smoke, and to get a break from the loud heat of drunk strangers. Then one morning, she messaged me.

Talia messaged me and told me that she used to be a nazi.

I was shocked. She had always read to me as someone who was compassionate, considerate - - things generally not considered nazi material. It took me a while to think of a response, but my mind was roiling with questions.

What did ‘used to be’ mean? For how long? How did you she get involved? What changed?

And why?

Why does she want to share this story now?

The following Monday, I pitched it.

White supremacy lives in Alberta. Both Alberta and Canada have long, rich, histories of white nationalism. Truthfully, it never really goes away. Even though the names and organizations will change, the ideological undercurrents are structural - - foundational - - to the ‘west,’ and are very much still active today.

Right now.

A lot of these groups have a public face that masquerades as something else first, then community members are drip-fed increasingly extreme views. The implicit feeds the explicit. Cults operate this way, and the cult gradually supplants all entire social spheres for prospective members, and, if they can, also make you financially dependent upon them.

As Talia told me her story, it was basically like a check-list for cult recruitment, including preying upon people living in the social margins. It’s through these tactics and processes that she was socially, financially, and geographically isolated from the outside world.

“I was never the popular kid in school,” she said. “I wasn't really making friends at work. I found myself just sort of working and going home, working, going home. And I didn't really have much of a life or anything going on. And I was very, very, very lonely.”

Then she met a boy, and he was into military history. REALLY into military history. So into military history, in fact, that he gifted Talia nazi memorabilia.

“He said, ‘I have a gift for you.’ And he hands me this package and I open it and it's a flag. A nazi flag. He explained; he said he wasn't a racist.”

No. Of course not.

Soon Talia was introduced to a man her boyfriend called “boss,” someone who seemed successful and charismatic, well-liked by other ‘WWII memorabilia enthusiasts;’ well-liked by the new and buzzing carousel of faces filling up Talia’s life. The three of them - - the boss, the boyfriend, and Talia - - started to go to gun shows together. She did not elaborate on what kind of wares they had on the table, but gunshows (in the states, at least)can become community hubs for the display and sale of nazi memorabilia. And theirs was a table that was fawned over often.

It felt like they became rockstars overnight, she said, and for the first time Talia felt popular. Wanted. Desired. She felt like she’d belonged, and, despite herself, looked away from the signs as they grew up around her.

Then, over several months, she was encouraged to leave her job and go work for the boss.

The boss owned a hotel in northern B.C., 8 hours away from YEG. The work was simple, the pay was good, and Talia was becoming more and more surrounded by people who gave her a sense of unconditional love. She was, in essence, being love-bombed by an entire fringe culture where the black metal and WWII axis iconography overlapped. She would attend parties where it started to become more and more clear who these people actually were and what their acceptance meant.

“Everybody's sporting swastikas, everybody's wearing bomber jackets [. . .] I was 100% isolated then, with just my boyfriend and this boss guy and just, slowly, still not even not even really realizing what I was doing and who I was hanging out with.

I just thought I found people that liked me and people that treated me well. The fact that [they’ve] got swastikas all over [their] jacket, it seemed irrelevant to me.”

Part of my own response to this was the burning question of ‘how did you not know?’ There are several times during our interview where Talia said that this whole process “went over [her] head.” Does this, in at least some way, a bid to shuck personal accountability? Responsibility? Perhaps. In the same way that I, as someone who signifies whiteness, maleness, cis-ness am choosing this subject matter and putting it up on this platform has implications. Choices are being made - pros and cons are being weighed. Whether or not Talia’s story deserves respect or ire (or, or neither) is up to the reader.

The choice to tell this story does not excuse the behaviour, or change facts. But Talia’s choice, implicit or explicit, to look away from the process - - this is also the nature of the cult. Groups like this cultivate the intellectual requirement for all the red flags to fade into the background. If they’re all red, they just look like flags. The warning signs are normalized, and made to exist on the periphery in exchange for social status, belonging, privileged knowledge, access, codes, and etc. After all, even nazis won’t come out and say that they’re nazis, despite being and embodying nazis by every definition.

“I remember a lot of the time, they wouldn't even necessarily call themselves nazis.

They knew they were. They knew they were sport and all the gear. They knew what they were doing. But their word for that was ‘we're nihilists.’

They're just like: ‘no, I don't hate a specific race, I hate everybody. I just want everybody to die. I hate the human race.’

And that's that was the message that they spread more often. But it was also littered with, of course, with racism, anti-Semitism.

[...]

I was just so surrounded by all these people who I thought were my friends and I thought loved me. And I thought these people know what's right. I was so into it and isolated with just them that it all made sense to me.”

Being steeped in these worldviews and codes increases the latitude of acceptance of the reality nazis are trying to sell. White supremacists are painfully aware of public perceptions of their ideology’s optics. Unfortunately, this lack of acceptance also feeds into the underground appeal of conspiracy theories. This scaffolds the populist alt-right and far right pipelines and points them toward white supremacy.

The suppression (perceived or actual) of nazi/neonazi codes in mainstream culture and media creates increasingly insular barriers between the ‘in-group’ and the ‘out-group.’

In Talia’s time, nazi web communities and music scenes had to go further and further underground, which compounded the isolating effect and fed into anti-Semitic and/or NWO narratives that rationalize and justify the nazi worldview and affect.

“When the music is underground and when the websites are underground, when the meetings are underground, you need to know someone who knows someone who knows them if you want to get into any of this.

It makes you feel like it's special.

It makes you feel like you're in this special little club, where you know how to communicate with these people and how to recognize them. Because you're all just one big family.

If you've got runes or swastikas or eagles tattooed on you, people can see you anywhere and just instantly know that you're a part of that family [...] and they just give you respect for like, no reason.”

It inches in, Talia said. One conversation, one idea, and one day at a time. And she described to me a specific moment where it became real to her.

Talia was at a house party with her boyfriend and the boss, with a number of other people around. The air became stiff, and still, and serious.

They put on a video.

The video showed migrants in Germany breaking into people’s homes, dragging women and children into the streets, attacking them, beating them. It was presented as a news broadcast, and echoed the weaponized, complex grief of the same country’s 2015/2016 NYE assaults. It was fuel on the fire for the populist right, stepping in-time with a surge in white nationalism. And it was being shown here to serve the exact same purpose.

“I believed it, and I bought it. Hook, line and sinker. I didn’t even think for a second [that] this is propaganda.”

nazis, both historical and modern, amplify and shape existing anxieties into a fear big enough to use as a weapon.

Hearing this all back, I remember something someone much smarter than me told me in my early 30’s:

The belief that you’re immune to propaganda is proof that it’s working.

It’s at this point in the interview that I asked Talia about the girl in the photo - - the person she became after the video. The girl that tattooed a reich eagle on her chest. For her, this was upping the ante on becoming one of them.

Being seen, being marked, being admired. She wanted to “look like them, act like them, talk like them.” This group identity had taken over her completely - - though she insists that she “never truly identified” with what she was putting on her body, the process, at this point and as far as they’re concerned, was complete.

She was one of them.

They’d won.

She was a nazi.

The isolation of working in the hotel had begun to take its toll, however. It was inconvenient to have to drive hours into town. In spite of everything, Talia still missed the lights of the city, and in the city there were people that could puncture the bubble she had been living in.

It was humbling, she’d said. Beyond humbling. Once back in Edmonton, she needed a place to work and where, of all places, did she end up?

Tim Hortons.

A workplace that is famously (or infamously) staffed by immigrants and temporary foreign workers. The irony is not lost on me, and, looking back, certainly isn’t lost on Talia. You can’t really walk around with a sense of racial superiority when you’re at the bottom of the totem pole in a fast-food coffee spot.

Once past that brief adjustment period, Talia began to witness a lot of things that contradicted her beliefs. As it turns out, her co-workers weren’t actually united in some mission to profoundly displace white canadians from their established racial hierarchies. By proximity alone, she came to understand who each person actually was. She experienced their human stories, with nuance, pain and complexity. Ultimately, she realized, everyone was out there, busting their asses at this donut mill simply because they needed to survive. No jobs stolen, no Trudeau voter base conspiracies, no pending reign of Islam.

Nothing more. Nothing less.

Just people being people, trying to live their lives.

“I started looking around me and like hearing the stories of everyone around me. A lot of them came from really shitty environments, [and they were] working their asses off to move to Canada.

They loved Canada, they appreciated Canada. They respected Canada. They worked harder than I ever had to work to be here.

There was something about just how happy they were to be here and how hard they had to struggle to be here. It really opened my eyes.I said to myself ‘people deserve another opportunity.’”

I found it doubly ironic that nationalism is ultimately what sparked the change.

In the months that followed, Talia got particularly close to Clifford, a gay man who came to Edmonton from Calgary. He told Talia about the homophobia that chased him throughout the province, and the gears continued to turn. This was the other side, the end result unfolding in real time. This is the world that nazis actually wanted - - her new friend sobbing on her shoulder about the very hate inked onto her chest.

“The people that are putting my friend who I care about through this and then have put my friend through this are the people I'm spending every day with are the people that I've surrounded my life with, you know, And of course, like working at Tim Hortons, like my uniform, like cover up my tattoos, nobody saw my tattoos, nobody knew anything.

[...]

I remember feeling so ashamed, all the time. And never wanting anyone at my work to know who I was. The veil started to lift for me, you know, And it's things started to fall away a bit.”

Someone much smarter than me said this, and it’s stuck: “the opposite of addiction is connection.” The world moves fast, and it’s hard to set down roots. So we go with what’s cheap, what’s easy. We take whatever rat pills we can get at arm’s-length doses and move on before else someone moves on from us, first.

Attention. Affection. Belonging. Purpose. Human need drained out and commodified in our shared post-modern condition, splayed thin and prescribed in too-small pieces to be bought and sold after signing the appropriate paperwork.

And lord, are we ever quick to sign.

Love, the product - - a community with conditions.

The repackaged addiction of modern life.

That’s what the nazis gave to Talia with one hand. The other held long knives behind their backs. She was addicted to the attention, the red fawning glow where she was met with a smile everywhere she looked. But of course she was - - she was one of them. And they were one of her. And they would surround each other. And it could always be that way, as long as you believed what they said.

“Think like them, act like them, talk like them.”

The opposite of addiction is connection.

The cult of white supremacy doesn’t have a monopoly on humanity. They can’t. It’s an ideology that relies on its removal and reduction, but real humanity, at its core, will always endure; it will always shine through, as long as a shred of empathy remains.

“Over the course of the three years I was involved with those people and my tattoos and everything else, I had made public statements. I had made public statements about myself. I had established myself in the city as a specific type of person. And this is what people knew of me.

[...]

If I want to get away from these people and if I want to, end this lifestyle and I don't want to be a part of these nazis anymore, so the only way I can fit can do this is I have to put nails in that coffin.”

When Talia left, it was “like fire.” And that fire burned bridges. She made them hate her; she crossed through all her old scenes (goth, alt, punk, metal). She cut down the cozy snares of white supremacy. She stomped on the toes of nazis edging their way around the fringes, looking for other people to bring into their fold, to bathe in conditional love and propagandize into oblivion. She doxxed the nazis, showed everyone who they really were and came with receipts.

Talia never wanted what happened to her to happen to anyone else.

“I wanted to make them hate me.

I wanted to be scum to them. I wanted to show them—I want to show the world that instead of being hate, I can be love.”

That was seven years ago.

And the photo of her still circulates.

Reintegration was a struggle. Talia’s life had been engulfed, completely saturated with white supremacy. Anyone who was a nazi loathed her, spat out her name like a curse. Anyone who wasn’t? They didn’t want to associate with a nazi.

“I had no idea who I was anymore.

I had been so wrapped up in other people's bullshit for so long that I just had no idea who I was anymore.”

Talia had to start small. She started a sticker collection. Her tattoos came off through a series of laser removal sessions and coverups. She stayed at home a lot. It took a long time to trust anyone again.

I think of our meeting at Steel Wheels.

She spent a lot of time alone; she had a lot of time to think and reflect.

“I have empathy and compassion for my former self because I know that person was really confused. And I understand where I was mentally and how I just wanted to be a part of something.

But I don't forgive myself.

I don’t forgive myself for spreading hate and I don't forgive myself for for really allowing myself to be infected by hate, because that's the way I felt. Hate is like a cancer. And if you allow yourself to be infected by it, it's going to spread through you and it's going to spread through other people that you touch.

That's the part I don't forgive myself for. I'm afraid that if I ever really forgive myself for letting it become me, maybe it'll become me again.”

Maybe it will.

Maybe it’s been me, too.

Talia’s story left me with a lot of questions for myself.

As a writer, as a film-maker, as a journalist (gonzo or otherwise), there are choices I make every day. Choices about visuality: where I look, how I look, when I look. Sometimes what’s most important is what’s missing.

How much do we look away from, and how much of ourselves do we trade for social acceptance - - for love, in whatever form it comes? How far do we compromise until there’s nothing left of us at all? How long can someone live in a worldview steeped with that much hate before it becomes real in your own heart? In the hearts of others? In the hearts of the world? And how does this pen write history around that?

Things to think about.

For me, anyways.

-zd